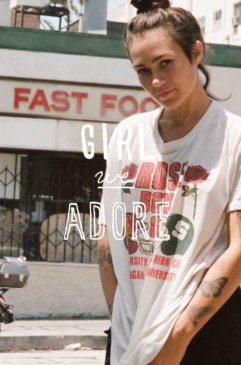

I’ve known Darren Rademaker, lead singer and founder of The Tyde and seminal indie bands Further and the Summer Hits, for the better part of a decade. I’ve seen him play more than a hundred times, at least, and it really never gets old for me. He just released his fourth album with The Tyde, appropriately titled Darren 4, on indie label Spiritual Pajamas, and the attention it’s getting seems to be blowing this prolific musician’s mind. “It’s just been interesting for me to see how many people are excited about it, that I put out another record.” Well Darren, we’re excited too.

Featuring Bernard Butler from Suede, Neal Casal from Chris Robinson Brotherhood, Richard Gowen from Jonathan Wilson’s band and Father John Misty, Bobby Keys, Andres Renteria, Dan Horne, and the essential Tyde members Brent Rademaker from Beachwood Sparks (and Darren’s brother), Ben Knight, and Colby Buddelmeyer, the album is packed with beautifully arranged “songs of sea, sex and sand sprinkled with goodbyes, divorce, truthful situations and perhaps a few laughs.” I met up with Darren at his Echo Park apartment and talked about the album, the haters, his Twitter interaction with David Crosby, and other stories from a life lived playing music.

The Tyde’s Darren 4 record release party is this Saturday at the Blind Spot Project with Tomorrows Tulips and The Pesos. It’s also Darren’s birthday, so if you’re anywhere near downtown, make sure to stop by. –Maya Eslami

WHAT YOUTH: Darren 4 is your first album in ten years. But you’ve been playing these songs live for as long as I can remember.

DARREN RADEMAKER: I’ve done all of them live except for one of them, “It’s Not Gossip If It’s True.”

When did you record the album?

I recorded the songs a bunch of times. But that version is from last year.

What do you mean by that version?

We tried three other times. Once, recording with Kenny Woods. And that was kind of like a Friday night party thing. That was the first attempt, way back in 2008. And we got a lot of songs out of that, but we never really finished anything. I think one song came out on a Burger thing. Then I tried to just go back to Rob Campanella’s – from Brian Jonestown – where I recorded all the other [Tyde] albums. But the idea was to do something different. So I didn’t really like the way that was going. I kinda stacked that. And we never really finished it. Then we recorded pretty much a whole record at this other studio in the valley with this weird guy- I don’t even wanna say his name, he was so lame. He offered us free studio time and at the very end he wouldn’t give us anything because he said he owned the masters, and we were just like, “Screw you. Thanks for the demos.”

Did you take the masters?

No. We just started over. We went back into Rob Campanella’s with the whole band for a couple days, with everyone playing at the time, the full band playing live with minimal overdubs, and we recorded what became this album. We took it and mixed it at Dan Horne’s Lone Palm Studio where Allah-Las record and everybody else records. That was great because Rob was busy, and me and Rob had mixed all the previous [Tyde] albums.

How was mixing it with Dan?

I liked the way that the band sounded recorded, so I just kind of sat there and gave him minimal instruction. I just let him do it, and I’m really happy with the way it turned out. I think it’s our best sounding record. But I mean, it was nice, because it was a combination of two friends, and that always works best.

Who else plays on the record?

My brother [Brent Rademaker] and Ben [Knight], Ben’s been on everything. He’s pretty much the only one that’s been there most of the time. Sometimes he hasn’t toured. And my brother’s been there a good 75% of the time, and Colby [Buddelmeyer]’s been there a good 75% of the time, too.

So core Tyde.

But it’s a new drummer, Richard Gowen [on the record]. Dan Horne plays pedal steel. Neal Casal, who never- he’s played with us a bunch of times, but never on any records. And he plays guitar throughout. And then we have the guest of Bernard Butler from Suede on the one song, singing and playing guitar.

That’s huge. How did that happen?

I became friends with him online, through social media, Twitter and stuff, we talked every once in a while. So I sent him the record because he liked our music, and I just wanted to see what he thought about it. Just the six songs that were done, I was gonna leave “The Curse in Reverse” off.

That’s the single from the album, right?

Yeah. It’s funny because it was a song that we left off the record. The time we recorded at that studio in the valley, Clem [Creevy] from Cherry Glazerr came and sang on some stuff with me, and I kind of had the idea for her to sing the high part [on that song]. And then I was trying to lock down Jenny Lewis to sing the high part, but she’s always busy. I just wanted a female vocal. But then I sent [Butler] the record, and he said, “Hey why don’t you ever ask me to do anything?” And the funny thing was, the guy that owns Rough Trade managed him. And I had reached out to Rough Trade before, and Rough Trade would tell me, “He’s too busy, he’s too expensive” or whatever. But then through social media, years later, he says “Why don’t you ever ask me to do anything?” And I said, “I did! I wanted you for so many years.” And he said, “Nobody ever told me. Well, next time.” And I go, “Well, as a matter of fact, there’s a song I didn’t finish.” And he’s like, “Send it.” And I thought, this will be perfect because I love his singing on his solo albums, People Move On – it’s one of my favorite records of all time. He ended up not only playing guitar, but singing with me. And I had yet to meet him. I’ve met him since, but we did it all through emails. That’s the one good thing about modern technology, you can send your tracks and someone can finish it in another studio. And then that song, like I said, was gonna be left off the album, I wasn’t sure how good it was, but a lot of people have told me that they like it. He just made it something a little bit better.

The album only has 7 songs on it. Was that intentional on your part?

We had recorded some other songs over the years. I just had this idea that I wanted [Darren 4] to be a ‘60s record, where it’s only 30 minutes long. So people start saying, “It’s only 7 songs, it’s an EP or a mini album.” No. it’s an album. It’s 30 minutes long, and that’s enough for an album. And that’s the way I like it. But after ten years, I think people would expect that you’re just gonna put out a record with a bunch of songs on it, or whatever. And I thought, “You know what, I like all these songs as it is, and there’s an order that I like to it, and I like that it’s short.” The idea was, get that done and start working on the next one. So it won’t be ten years before the next one.

I feel like you’ve had these songs for a while, and now was the time to put them out into the world.

That’s the thing, when the time is right, it’ll happen. I really could’ve worked faster, but for some reason it just wasn’t right, and that’s what’s nice about it finally coming out. It’s been ten years since the last album. That was before Spotify and all that stuff. It’s just interesting that people still want it, and that’s why there was really no purpose in doing CDs or anything like that. The idea was just to put it out on vinyl and then people can download it if they wanna download it. If they want to pay to download it, because obviously you can already get it for free. it’s just the way it works, you know? And it doesn’t matter so much. We’re not making it to be famous or to make money, although the money part would be nice. It’s just been interesting for me to see how many people are excited about it, that I put out another record. And I’m excited about it.

And it’s only your fourth. Is that why it’s called Darren 4?

Well, that was always a thing, because [the first Tyde album was called] Once, then Twice, the third one was called Three’s Co. because we couldn’t call it “Thrice” – there was an emo band called Thrice, and we just thought that was stupid anyway. And then when it came to the fourth, the reason it’s called Darren 4 and I’m on the cover and stuff, is because there was a time when maybe this was just gonna be a solo record, because there’s been so many changes [in the Tyde]. But then my brother was back, and enough Tyde members were back, to call it a Tyde record.

Also, Scott 4 by Scott Walker is one of my favorite albums of all time, and obviously we sort of copied the artwork on the cover. We used the template along the lines of the way the Clash, London Calling, is an Elvis Presley record; it’s not the same picture but it’s sorta the same fonts. And by no means do I think it’s as good as Scott 4, which is a masterpiece, but it was also just another “fuck you” to the haters that will be like, “Oh god what does he think he’s doing.” But most people won’t even realize. Most people just like it. The only people that will say anything about it are the haters. People always associate us with Felt, but there are a lot of people who are hardcore Felt fans that think they’re indie kids and they know everything about Felt. But I’ve been listening to Felt before they were probably even born. And Lawrence [Hayward] from Felt came to our show in London, and we know he likes us, you can see it on YouTube where he talks about us, and like, if it’s okay with him, why is it not okay with you? A lot of people compare us to Teenage Fanclub, and some of the haters are like, “They think they sound like Teenage Fanclub.” Well Teenage Fanclub, they like us. They like our music. So there’s this sort of elitism and “what’s cool” and “what’s not cool” that goes along with indie music. And the funny thing is, the same people that might go and see these bands might not listen to our records, but the actual bands themselves listen to our records and like us, and that’s some sort of minor victory and poetic justice. But that’ll always happen, in any form of “art” or whatever it is.

What, the haters?

The haters. Why is it that people pay attention to another artist so much? Like they talk about my brother’s band Beachwood Sparks and how they were so ground breaking in country rock and what became popular with other bands took it to another level. But they just did it before that, and the timing wasn’t right or whatever. And we’re the kings of the timing wasn’t right. I just don’t know why the same people that listen to a Father John Misty record don’t listen to my record.

It’s all about the consumerism of it, and the marketing and how much money you have and all that bullshit.

What’s interesting with my old bands Further and the Summer Hits, when we were doing them, nobody ever really gave us that much respect, even though bands like Pavement and Sebadoh took us on tour and we played shows with Stereolab and other bands like that. But now, twenty years later, we have it. When the Summer Hits reissue came out last year, that was such a small bunch of 7” and the original record run was so small, it just made me so happy because we achieved what we did. When we were making the Summer Hits, we’d listen to a lot of ‘60s and ‘70s music and we would say, “Wouldn’t it be great if in twenty years’ time, if one kid finds this record and likes it as much as we like it.” Like some obscure thing from the ‘60s or ‘70s that no one knows about. That’s the good thing about music. Although there’s way too much now, way way too much to really listen to everything you could possibly wanna listen to, so people are just overwhelmed. And now, you can probably go online and find anything you want. But you know, vinyl’s so “back” and it’s always gonna be a preferred form of listening to music. But just like cassettes came back with Burger, CDs will come back.

CDs suck.

CDs don’t actually sound that bad. Everything sounds different everyway you listen to it. The thing about it is, it just doesn’t matter. A lot of bands are like, “We have to record in the same studio as the ‘60s and it can only be on tape.” Like, no one cares. Other musicians care, but when a person’s listening to a song, 90% of people- more than 90% of people are not thinking about how it was recorded or how they’re listening to it. Of course I think vinyl sounds better. When I deejay I only play records. It would be easier to bring a computer and all that stuff, but there’s just something about holding it, putting it on, collecting it, whatever it is that makes it different.

How did you record the final cut of Darren 4?

We recorded on digital and we dumped it to analog and mastered it from analog.

It sounds super clean.

Well, there’s a trap. Like Ariel Pink has come to me a couple times and said, “Why don’t you make records that sound like Further?” Like, “That sounded so cool.” But I already did that. Lo-fi is cool, but the thing is, either have it sound sort of crappy and ‘60s or lo-fi or whatever you wanna call it, or have it sound really, really good. But the middle ground is something that’s so hard to avoid. We call it “local band feel” and constantly ask, “Does it sound like a real record to you?” Your own record’s never gonna sound like a real record because you were there every step of the way. But it’s nice to hear what other people think. And other people come to me and say, “Wow it’s your best sounding record.” And that makes me happy. And all the reviews have been good, and that makes me happy. For whatever reason. Song writing and trying to portray anything is kind of embarrassing. You’re an easy target for people to make fun of anything that you could possibly do. And it’s hard to overcome that. Not to have a message, but to the younger bands that are friends of mine, the one thing that’s important is, “Is this song about something?” Even if people don’t get what it’s exactly about. Does it relate to people in some way? Does it come from a truthful situation? You could write a fake song about butter and it would be funny and good, maybe, but to have a song that’s really about how you feel, and what’s going on for you at the time, for whatever reason, is the best.

The thing is that- like I’m on the cover, I’m the one that’s like “The Tyde” and there are bands that have names but it’s really just one guy that’s the main guy and writes all the songs. But I would be nothing without all the guys that play with me. Really great musicians play with me. That’s another thing that’s important to ask: Do you wanna play in a band because you wanna meet chicks and do drugs and have sex and be famous or whatever? Or do you really care about the music? Sometimes people forget, like you have to practice. I’ve played guitar for forever, but I still have to practice. And I want everybody that plays with me to be a good musician. Our voices might not be the best, our harmonies- people like to compare us to the Beach Boys, but we’ll never sing that well, we just can’t. But we’re doing our own version of it. In bands like the Pastels, none of the vocals are that great, but it conveys a soul to me even if it’s off tune or out of tune when Stephen [McRobbie] and the girls sing together, it just makes such a beautiful sound to me. It’s soul music for me. That’s what I hope I’m doing. Like I never think I’m a great singer, I wish I could sing like Scott Walker, but there’s no fucking way. He’s like Michael Jordan. And it’s hard. Just try and be yourself. One of the things we always try and portray and promote is California. We love California. We love surfing. But our songs are just as serious as Nick Cave’s. Just because we’re not wearing suits and being all serious in the studio, we take it just as seriously. But also, it should be fun. It should be funny sometimes, too. Like Bob Dylan, it’s funny sometimes. It’s fun.

I remember the first time I ever saw you play “Situations” and you sang “motherfucker” in the chorus, and I was just laughing, in a great way.

I put that line in the song, and I thought it was weird because once before, this super famous journalist Everett True, he’s super hard core. He’s one of the most influential writers throughout punk, post-punk, whatever, and he, for some reason, was always kind to Further. And on the first album with the Tyde, in his magazine that he had at the time, he reviewed it and he said, ‘”All My Bastard Children” the song, is a perfect song, except for the part where he starts talking about drugs.” And I thought, when I put the line “It’s a motherfucker”- I had just gotten divorced, and I was going through all this different shit, and I kept finding myself in different situations. We played with My Bloody Valentine at their All Tomorrow’s Parties Nightmare Before Christmas in England with some of my all-time favorite bands. It was the best festival we’ve ever played. And it was December and on the coast of England and I wore shorts on stage, and kids were coming up to me being like, “I can’t believe you fucking wore shorts!” And that was one of the first times that we played that song, and other people would come up to me and say, “That “motherfucker” song! What was that “motherfucker” song?” That’s the one thing that people remember, and sometimes I get embarrassed, what are my parents gonna think of it, that kind of shit, like still, even though I’m old, I still think, “Ahh shit, what is my dad gonna think about this when he hears that”. A lot of people cuss in their songs, some people don’t cuss in their songs. And it’s just strange that way. But see, people remember it. But we’ve played that song for so long, and it’s funny that now it’s the song on the album that we don’t play live.

Tell me about the song “The Rights”. That one’s always reminded me of Neil Young / Crazy Horse.

One review already said it sounds like a cross between “Cowgirl in the Sand” and another song, I can’t remember what song he said it was. But my idea behind that song was that it was a cross between a David Crosby type song, off David Crosby’s first solo album [If I Could Only Remember My Name], like that kind of feel. Which is still Neil Young – he plays on it.

Didn’t you have a thing with David Crosby?

I had a Twitter interaction with David Crosby, which other people I know have, and it wasn’t good, and it made me feel like, god, way to ruin it for me David Crosby!

What happened?

Further covered one of his songs, long before people were listening to David Crosby that considered themselves cool or hip, you know, people didn’t listen to David Crosby in the ‘90s. And we covered one of his songs on our record. But we did it in the style of this band we liked called Flying Saucer Attack from Bristol, England, where they were the noisiest, lo-fi, just white noise going on, but there was still pop songs underneath. And they covered “The Drowners” by Suede. You can barely tell what the song is. But it sounded kind of cool. So we did that with a David Crosby song. So one night, he was on Twitter, and he was talking about, “Anybody have anything to say to me?” because he’ll take questions sometimes. And I said, “Yeah did you know we recorded one of your songs in 1993 through a vacuum cleaner?” And I sent it to him. And he was like, “Pretty much crap.” And like, he’s right, it’s horrible, but he doesn’t understand the idea behind it. But I was just stoked that David Crosby interacted with me on Twitter. Anyway, that song “The Rights” was meant to be a cross between a David Crosby song mixed with a Brit-pop Suede song, because the chorus is like a cheesy Oasis/Suede type chorus, that was sort of my blueprint for the song. And of course people just say it sounds like Neil Young, which it kind of does, because the guitar playing. It’s a slow boogie-rock jam. But yeah, I like that song.

Does that bug you when people compare your music to another musician?

No, I think it’s great. I can’t remember what the other song some guy compared it to, because it blew my mind. But that song, “The Rights” – there’s a surfing thing in California, all the point breaks are rights, basically, I mean most of them. There’s a couple places you can go left. But in general, that song, it means “we got the rights.” But it also means, you have the right to do anything you want to do, as long as you’re not hurting anybody purposefully, you know what I mean? We get tagged with the “retro” rock thing, but do people listen to the words? Because “The Curse in Reverse” talks about phones syncing. I remember when I was writing that song, that was back when you had to plug in your iPhone to your computer to download your pictures or whatever, and if you were doing that, your phone would go dead for like a half hour, and it felt really bad, like, “Is someone trying to get ahold of me? I need to call somebody but I can’t do it because I don’t wanna stop the transfer.” And so, even though this music is influenced by retro music, we try not to make it sound that way. I would love to make a techno record if I knew the right people to help me do it. John Anderson and I have been working on a project together, kinda like my solo record, and we wonder, “You think Drake could sing this song?” “You think Selena Gomez could sing this song?” I like that just as much as I like the most obscure thing that I listen to. I just like, if a song is good or whatever, I think that’s the best thing. Going back to indie circles or whatever, in the ‘90s, if you had a Led Zeppelin album, people would make fun of you. You were only supposed to listen to one kind of music. And now, everybody listens to all kinds of music. When we started off in Florida, Brent and I were the only ones [open to different music]. We’ve done more than anybody else in indie rock, at least in our little town. We opened for Duran Duran, we opened for Billy Idol, and the Dream Syndicate, and X, and we just had to get out of there. Then when we moved here, we had the dream where we got a major label deal and everything was perfect.

When’d you move to LA?

1987. In this article, this interview with Norman [Blake] from Teenage Fanclub, he tells a story about how they were on Geffen Records – our first band, Shadowland, out here was on Geffen – he tells a story about how for the album Thirteen, the album cover for that is a deflated soccer ball, kind of a weird cover. But Geffen had this cover, because it was called Thirteen, with this young girl wearing a tank top and like nail polish running down her shirt or something that they wanted to use. And [Teenage Fanclub] said no. Then Geffen said, “Well this is what we want, so we’re not gonna give you as much promotion if you don’t do it”. And Norman Blake just said, “Fuck you, then”. And we had a similar situation when we were on a major label, and that’s why when we went back to doing indie music with Further after being on a major label, none of the indie community wanted to accept us because they looked at us like we were this band that was on a major label that all of a sudden wanted to jump on the grunge bandwagon or whatever. But we had already put out indie records in Florida and put out shit on Sub Pop in like 1981, so, we’re more indie than you. Or whatever. But a lot of those people, even some famous bands, they would never accept us. But now, they’re finally like, “It’s pretty good.” Because all the drama around it faded, and all that was left was the music.

NXT

NXT