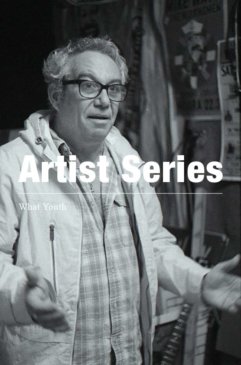

I’ve always loved Jamie Brisick. For many reasons, but one important reason being that along with Derek Hynd and us, he considered surfing to be one of the most conservative, uptight and close-minded of all the sports. This should sound baffling, because surfing was born of rebellion and outcasts and characters, but it’s changed. A good debate with Jamie on this topic is always enchanting.

Which leads me to another exciting thing about Jamie: he recently finished writing and releasing his new book about ex-professional surfer [formerly] Peter Drouyn’s transformation into Westerly Windina.

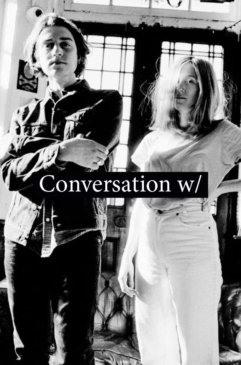

We invited Jamie over for coffee talk. And it was enlightening and inspiring.

You can purchase Becoming Westerly, and I promise you should, right here.

What Youth: What is your background in surfing?

Jamie Brisick: Well I grew up in Los Angeles and started surfing in the late ’70s. Competed in the NSSA and then turned pro. From 1986 through 1991 I was on the pro tour. My career ended abruptly. I was living in Sydney at the time and I started writing for magazines and I got interested in “surf journalism.” Went back to Los Angeles for a while and was the Editor at Surfing Magazine for two years. Then moved to New York for 10 years and along the way I did a lot of different writing for a lot of topics. But surfing was always there. When I found out about Westerly Windia, or Peter Drouyn living as a woman I was fascinated and went to Australia to get the story.

What attracted you personally to this story in particular?

I grew up surfing Malibu — and while he was long gone by the time I got there — Miki Dora was always there. The ghost of Dora loomed at Malibu and the many characters who were on the beach that I looked up to were all kind of the decedents from the lineage of Dora. So there was always this irreverence, and there was kind of this challenging the status quo that I liked. And it felt rebellious. Surfing felt really rebellious, and that was the world I came into. Since then I’ve literally watched it become exactly the opposite. It almost feels like like right wing or extremely conservative now. And that’s disappointing to me. So a lot of the surf journalism I’ve done, a lot of the writing about surfing I’ve done, I’ve kind of tried to comment on that at some level. So I guess when I found out that Peter Drouyn is now Westerly Windia, and most of the surf community thought it was just a joke, I was so happy to get in there and kind of grind the axe on Westerly’s behalf because I felt like it was great.

Who was Peter Drouyn to you prior to this endeavor?

Peter Drouyn represents the exact thing I was talking about with Miki Dora. Peter Drouyn really looked up to Miki Dora. He was outlandish and eccentric. He had a wild imagination. He was a visionary. When I first encountered him he put on something called The Super Challenge in 1984. He called out Mark Richards — who at the time was the four time world champion. At the time I think Peter Drouyn was 35 and was past his surfing prime and he called about this thing called the Super Challenge. I think he was drawing from the Muhammad Ali and George Foreman’s “Rumble In the Jungle” with this idea of this massive show: one on one and all this drama. He had taken out an ad in a local magazine and he was naked, and he only had underwear on, and he was slathered in ketchup, and he was standing in kind of a crucified position. There where all these taunts on the page like, “I will kill or be killed!” to prove he was the master of the surfboard. It was like boxing or wrestling or something like that. We were once in South Africa at the same time for the Gunston 500 in 1989. I got third, I lost to Brad Gerlach in the semifinal — which was a big result for me. Peter Drouyn was there and was the oldest guy in the contest and he was really not that interested in the contest. He was actually there looking for wife and had actually put an ad in the paper essentially saying, “Pro surfer seeks wife” and he ended up finding a wife out of this whole thing. He held like a giant casting and found a woman that he would end up marrying.

When you met Westerly, what was that interaction like in the beginning?

So in 2008 Peter Drouyn came out as Westerly Windina on Australian national television. It was a huge spectacle and it was in the newspapers, as he was the first transgender surfer. But the thing is Peter Drouyn was someone who loved to shock people, so most people thought, “Oh this is a little charade.” They thought it was temporary and that it was probably a publicity stunt. This isn’t real. So I went out about a year after that to write this profile of Westerly for The Surfer’s Journal and she was legit but she was really kind of campaigning for herself. She was looking to spin the story of her metamorphasis from Peter into Westerly. I started fact checking and getting quotes from Peter’s peers and every single one across the board were basically saying, “You’re getting duped.” That I was a journalist who was going on a ride and that was going to be laughed at in the end. It was kind of weird because I had the reputation as a writer at stake. If I’m in support, I’m sort of trying to usher the story along, it better be legit. Or at least I hoped.

Before this point what was your relationship with the gay and lesbian and transgender community? Were you curious? Or are you meeting this person and going on the journey with them and learning as you went?

I grew up in Los Angeles in the punk rock scene. I grew up around a lot of really open-minded people. Homosexuality was not a problem at all. I had plenty of friends who are gay. I hated that the surf community is so homophobic. I remember one year I was working at Surfing magazine and we had a house and everyone was being packed into rooms and there wasn’t enough room for everyone. So I went in and announced I was bi-sexual right off the bat to everyone just so I’d get my own room. It was like, “Clear out! It’s the bi-sexual guy. We can’t go near him.” It worked and I got a room to myself. I think it’s really, really sad that there’s so much close mindedness in the surf community. I won’t deny Westerly was absolutely strange, and she was one of the more outrageous people I’ve ever met. Yet so vulnerable and real in a way that most people aren’t. There would be a lot of times I would be walking around with Westerly and I would see people doing double takes as we were a couple. I forgot that this is someone who is this sort of a pariah, where every person is sort of going, “Oh my god, look at the freakish person.” It just didn’t feel like that after meeting her. It was more, “Oh, you’re an interesting person.”

This is not a biography that you just read and go: Oh, there’s the story. It has memoir elements, and when you’re traveling with her, the world around her is very real. There is tension there.

Yeah. One thing that happened along the way is I started to realize when I started researching this in 2009 is that there were a lot of ex-pro surfer dudes in their ’60s. And a lot of them were really skeptical, and a lot of them refused to call her Westerly. In the five years or so they’ve really shifted, I think in part of transgender awareness, but the other thing is that they’ve seen that this is very much for real. It wasn’t an act that could be sustained for this long. You would have to break character at some point. Westerly has not broken character. In fact she’s gone the whole way. It’s been nice seeing, and I won’t mention names, but some really respected pro surfers who were skeptical and kind of had disparaging things to say, are now very sympathetic. They want to give Westerly their best. I’ve interviewed them later on they regret what they said to me three years ago. They’ve changed their tune and they want to wish Westerly well. So that’s been nice to see.

As you’ve gone through the process of the history of surf culture, have you noticed the grips of the conservative outlook continuing to tighten?

I think people are becoming more open-minded. I think at one point surfing was it’s own little subculture, and as it grows it kind of self pollinates into overlapping circles with other cultures. Like with What Youth you can turn a page and it looks like a surf magazine, turn another and it looks like a photography magazine, and another looks like a visual art magazine. As surfing grows it brings in more character, and that might bring in some more conservative stuff, but as it expands it also brings in more open-mindedness. There was a documentary made over the last couple years called, Out In The Lineup that was about gay surfers, and I thought it was great. It was winning not only film festivals all over the world, but surf film festivals were really pleased as well. That to me was a nod of approval as apposed to, “What’s this doing in our culture?”

Shifting gears slightly, what is your take on modern competitive surfing?

I have a guilty conscience about watching the webcasts and surfing events. I love them and I think they’re fantastic. I can get so locked into them. But the problem is that surfing is like cricket, or like Wimbledon, like tennis in the sense that it’s days of your life. As where a basketball game is really quick. I kind of go in and out. But lately I haven’t been watching as closely as ever. To be truthful the thing that’s engaged me always in surfing is knowing the guys, knowing their stories, so I can personally root for them. And in some level, and I haven’t done this consciously, it’s just been doing it while I was working on projects, but there are so many great surfers out there today leading the WSL and I don’t know their personal stories so well, so there for me, there’s a really cold figure on screen compared to a really warm figure. I guess I just operate with so much nervousness and anxiety cause I spent so much of my life on the beach, and I’m a writer now, and so I almost feel that I’m making up for a lot of lost time. So reading and writing are taking up all my time. It’s sort of like the amount of time I want to give to my life in surfing is actually when I want to go surfing or when I want to be writing something about it. It’s like a guilty pleasure watching it. It’s great, but I just don’t always have the time.

NXT

NXT