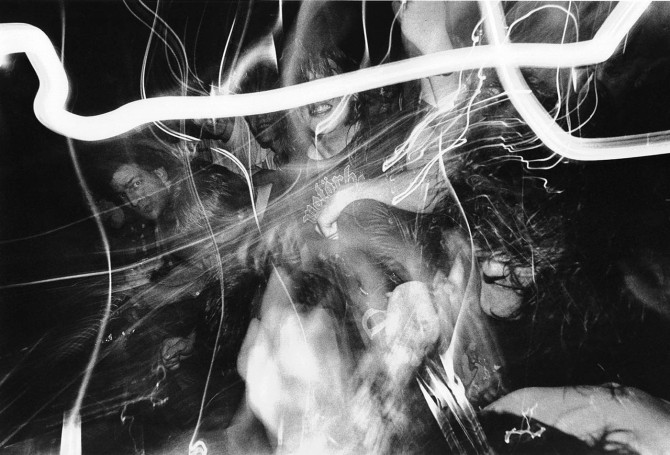

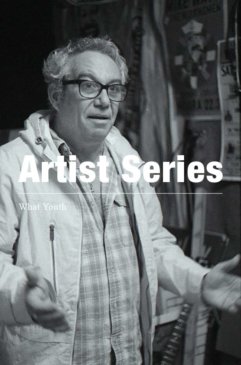

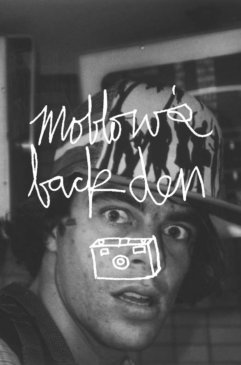

Mudhoney. Soundgarden. Pearl Jam. Nirvana. Sub Pop. Seattle. Photographer Charles Peterson found himself a young man in the trenches of what may be one of the last underground, analog indie music scenes we get to see come together the old-fashioned way. And he found himself there not playing the music, but documenting it. With camera and film.

He has taken some of the most iconic images of Nirvana and Kurt Cobain. And more importantly, his photographs capture youth in its purest form. We had the chance to talk with Charles from his Seattle home and asked him what it was like documenting a time that we still, to this day, romanticize as one of our more authentic major cultural movements. And it came from the Northwest.

Read our interview with Charles and check the gallery of some of his images below.

WHAT YOUTH: Before being a part of the music scene, how did you get introduced to photography?

CHARLES PETERSON: I lived with my grandparents, you know, product of a divorced family in the ‘70s, and I had an older uncle who had a darkroom in my grandmother’s washing machine closet. I was fascinated by it so I’ve kind of just done photography since I was about 8 or 9.

So you learned the old-fashioned way, with access to a proper darkroom. Oh yeah, there was no other way. During junior high and high school I worked on the newspaper and yearbook taking photos and then off to college and studied photography at the University of Washington.

Were there any certain aspects of photography — whether it was portraiture or landscapes — that you focused on at that stage? I didn’t know what I wanted to do except at the time photograph my friends’ bands. Some teachers were into it and others not. But I needed a subject; I’m not the kind of person who goes out and imagines something and then creates it. I needed something dynamic happening in front of me. And, well, my friends’ bands were pretty dynamic, so I just started to develop the style around that.

So you were shooting bands before the whole scene developed around you? Yeah I was photographing some of these individuals when there were like only 25 people at the show. When did it turn into a job for you? My relationship with Sub Pop was kind of nebulous. Initially they hired me to just do a little bit of everything and I got paid an hourly wage. When there was a little bit of extra money they’d slide me some for the photos for the records that I took. But for the most part, I wasn’t getting paid on a per-job basis, I was just going out and doing it and if something worked, you know, and certainly if they had assigned me something for one of their bands they would pay for materials. But it didn’t really become “work, work” until the early ‘90s, and especially once I went totally freelance and I was doing a lot more music editorial stuff, a lot of Guitar World pieces and things like that.

Things that were more assigned? Yeah, more promo photos instead of just like, “Oh, we need a promo photo, let’s see what you’ve got.” It was more like, “Let’s go out and shoot a specific promo photo.” A lot of people are under the impression that I sort of parachuted in at one point but literally Mark Arm [of Mudhoney] and I were roommates in college when he was in Mr. Epp and the Calculations. Kim Thayil and I would go out for Chinese food when we were in college; he was in this band before Soundgarden. I just happened to be fairly handy with a camera and interested in it and it went from there.

Was there ever a point when you became conscious that you were potentially documenting a piece of history? like, did you ever realize what you were documenting could have a global effect? Yes and no, probably not as much as I should have. It’s rock ‘n’ roll, it was fun and it was dumb but nobody really thought…well, it wasn’t until Nirvana totally blew up that it was like, “Oh yeah, this is something different here.” Even then, I thought, “Oh well, Nirvana’s huge now, like five years from now nobody will know who they are. They’ll put out a bunch of records and just do whatever, be like Sonic Youth is now or something.” But nobody thought at the time that they would be up there with Elvis and The Beatles.

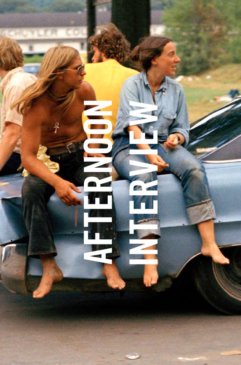

Do you look back on that time and giggle to yourself… It’s revered as this massive turning point in culture in a way and our generation is so fascinated by it because it’s this time period we revere, and we see these photos and we can kind of relate to them now. Do you look back on them and go, “That was just us in this really sketchy bar, sweating on each other?” Yeah, for sure. It was really just making it happen. It was kind of the last big rock movement that was pre-digital so you had to shoot film, you had to go to the record store, you had to hook up and call each other on regular telephones, and so it just happened a little bit slower over time and it was able to really nurture the talent that was there. I think that’s why people are maybe so fascinated by it.

Were you a big fan of all the music and completely ingrained in all that culture too? I spent a lot of time, too much time, in record stores. We were all very well-versed in the history of music, at least rock ‘n’ roll music. Mark Arm and I, when we were roommates in college, we would sit around and listen to Can records and then we’d listen to Black Flag records and then we’d listen to Brian Eno or we’d listen to The Birthday Party. So Mark and I were kind of into everything and a lot of people don’t pick up on that. Many of us knew our musical roots; it wasn’t just thrown out there. There are influences there that some people may not pick up on. The Doors were a big influence and of course none of those guys would admit to that because certain bands…just because of the nostalgia aspect of them. You listen to Green River and then you listen to the first Doors album and you’re like, “Oh, OK…” I’ve just been listening to Ram, the Paul McCartney record, and I’m like, “Whoa, a lot of that is very proto-grunge.” There’s one song on the Deluxe Edition that obviously nobody would’ve ever heard of then, but it’s so proto-grunge, it’s so Nirvana ripping this off. It’s pretty great actually. On a couple occasions, Kurt talked about The Beatles being an influence. It’s like, “OK, here’s where you hear it for sure.”

With someone like Kurt and Nirvana, were they introduced to you or did they just start popping up at the shows? They were outsiders at first, so we were definitely introduced and I was flown out to take a promo picture for them for the label. The scene was pretty well established by the point that they had come along and they just blew it apart.

Did you tour with them full time? I wouldn’t say I toured with them, but certainly down the West Coast and I showed up in England a couple of times. So looking back, I photographed Mudhoney a lot more and several other bands more than I did Nirvana. In true hindsight, I would’ve photographed more Nirvana, but honestly, toward the end of their career, they were not a fun band to be around compared to some of the others like Mudhoney, Pearl Jam, or whatever. Nirvana were pretty dysfunctional. I saw a couple of their later shows, with all the stage props, and I just found them kind of depressing.

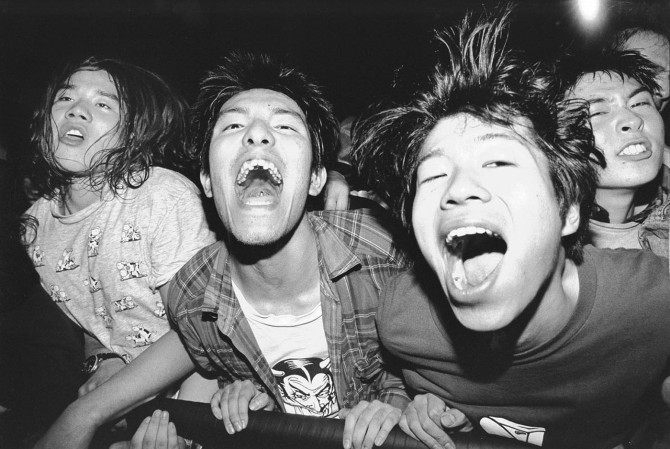

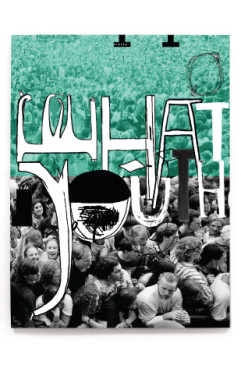

Looking at these bigger crowd shots you have, are these festivals? You have an intimacy in these photos in large group shots. I always made sure to take crowd pictures. The best compliment I’ve ever had was probably about 8 years back, I had an exhibit in Virginia at The Chrysler Museum, very old, but they did a Touch Me, I’m Sick exhibit, named after my book. And a lady, probably close to 80, came up to me and said, “You know, I really know nothing about rock ‘n’ roll but after seeing your photos, I feel like I do now.” I want to put across that feeling of what it’s like to be there at the show and down in front and the band going crazy and the audience going crazy and how they sort of come together at points. One of my most popular fine art print sales is the one of the big stage diver jumping off the PA and I think for a lot of people it’s an iconic photograph, it kind of sums up the generation.

To see more exclusive Charles Peterson imagery pick up What Youth Issue 11 here.

And watch Charles Peterson in this Rights Refused video presented by KR3W:

KR3W “Rights Refused” with Charles Peterson from KR3W DENIM on Vimeo.

NXT

NXT