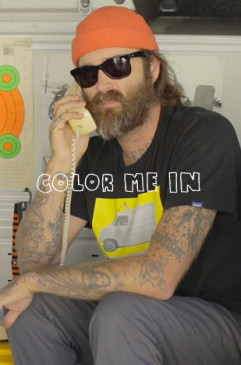

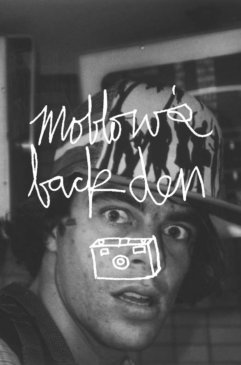

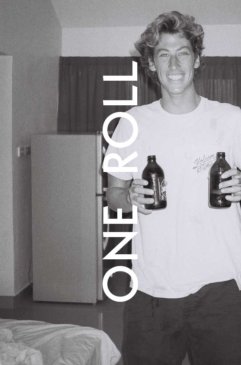

When people walk through the What Youth HQ they often notice a few skate photo zines we have in the shelves. They were made by Ryan Allan. Ryan is a skater’s photographer. He’s a skater. A punk. Opinionated and always pushing skating and skate culture to evolve and represent itself. His photography is the same. Intimate, iconic and real. We talked to Ryan about maintaining integrity in photography and how important it is for our small waves of rebellion to grow as a means of reinvigorating suddenly mainstream subcultures.

WHAT YOUTH: You finally get off the tarmac?[When he’s traveling, which he does often, Ryan posts photos of tarmacs around the world].

Ryan Allan: Yeah, I’m stoked. And I always likehearing from you guys…

But we’re surf dorks mostly. Tell us a bit about your background, all I know is you make fun of surf dudes and skate dudes respect you, you take epic portraits and action photos. How did you manage this?

My dad was an amateur photographer. He’d photograph us all the time. Even do scripted shots just for family photos. He remade the classic scene of E.T. where they hide E.T. with all the stuffed animals. He did that with my brothers and I when we were young. I learned a lot about documenting from him.

What about skateboarding?

I lived in a small town made up of mostly ‘80s metal dudes in denim rock jeans and I just wore skate clothes and skated. Shot photos of my friends. There was a lot of beef with me at school and I got kicked out in about 11th grade. I’m from a small town called Grimsby in Ontario Canada. The town was just basically known for it’s punk band Sector 7.

Core.

In what would be 12th grade I skated and snowboarded with my friends all day and got my high school diploma through a photography portfolio I built during school. I got into a college with that portfolio, and did that for two years. I met a lot of inspiring professors who were all just rad working photographers. They told us that this diploma stuff doesn’t mean shit at this point in photography and that we needed to get our portfolio done at the school and get out there. So I didn’t even finish it. I just went up to my last couple months and got a job for a snowboarding magazine in Toronto, Canada. Then I got really into shooting snowboarding, but ditched that due to the cold and snow. I wasn’t that psyched sitting at the bottom of a half pipe freezing my ass off. So I focused more on the skate stuff. But then that mag went out of business — like they all do… no offense.

No we’ll be here forever and ever. We don’t worry about that.

Through that I was offered a job to be the editor by a regional Canadian skate mag. Within two hours sitting with the publisher things went from running a little zine to, “Hey you’re running a full-color magazine on your own…do you know what you’re doing?” Of crouse I was like, “Yeah, sure.” Full bullshit.

That’s how we got here too. Fake it until you make it.

All I had was one of those crazy-colored, candy purple and clear iMac computers and was now in charge of a full-color legit skate magazine. At the time most magazines were run by distributors, so it was always political with who got shots and all that. And there I was running the first non-biased, distributor run mag. We were based in Toronto — full East Coast skate mag. We were some of the first guys saying, “I’m going to run this because someone rides for so and so’s company. I’m going to run this because it’s sick.” Even guys who worked for other magazine were sending us stuff because a lot of their stuff wouldn’t be seen due to the politics, so the magazine had content right away. It gave a lot of new companies outlets to advertise. But I burnt out on that pretty quick, though. It was a give-up-your-life-to-make-it-run job. You’re chained to a computer. I was lead design. Photographer. And copy editor and writer. As you do when you start, you do it all. I would sleep in the office in a high rise in Toronto. I was bummed that I wasn’t skating and I was losing touch with skateboarding and what was going on in skateboarding.

So what did you do?

This was around the time Mark Appleyard was blowing up. He mentioned being able to get me a job in California. That linked me up with Circa Footwear who’s team at the time was Muska, Jamie Thomas and Mark. I mean everybody was there. I moved to California and that’s when real shit started. I knew everyone from working at the magazine and I started working at Circa doing everything: designing shirts and then worked my way into shooting and being the lead photographer within the year. That’s always been my M.O.: do what you need and figure out how to in through the backdoor or whatever needs to happen to do more of what you love.

I notice when people come in here, Rowley, Dylan, Jamie Thomas, when these guys come through, you command respect and they’re stoked to see your work around the office. Is this the era when you established all that?

That was the nice thing. This is the number one lesson in skate and I’m sure it’s the same in surf: When you see someone rising and doing well and you can help, you get with them and help them and give them an outlet. When you have that and you’re with the dude who’s “the guy” and you have that relationship and you’re right alongside them. And as long as you’re producing good work, you can ride that. It didn’t hurt to walk into Circa — a place filled with icons and guys who are still relevant today. Muska Rowley Thomas, etc. Also having an editorial background was helpful. Guys like to see that, it means you know the ropes and work hard.

Does that help you establish an authentic look as opposed to a commercial look?

I get passed off as a hater a lot. Because as an editor of the magazine I would just call out stuff that was wack. And you have to. I got a lot of heat for that in Canada because when that tall-tee, white t-shirt down to your knee shit was going on, I would have a problem with that and wouldn’t run that in the magazine. Ultimately the world knew it was a wack trend, but I took a lot of heat for it.

You have to be able to stand up and know you’ve earned that opinion through hard work and lead skateboarding in a stronger direction.

Sometimes it comes across like I’m a dick, but I’m willing to take a little of that for the greater good. I may talk a lot of shit, but I’m also the guy who thinks all that shit needs to be there too. You need the shit you’re not into. The weirdos and the jocks and what not. It allows us to all be different and allows the Dylans [Rieder] and others to rise up and look awesome. Without it would be generic. If everyone looked the same, there would be nothing to rebel against. Nothing to stand out from.

And these cultures are about evolving, changing, rebelling.

When Dylan puts out a shoe or Ben Nordberg put out a commercial where he’s looks different, I look at comments and message boards and what people say in skateboarding’s mainstream, and it’s fucked to the point where if you don’t look like Billy the quarterback when you’re skating, then people hate on you. Which brings it back and I think, that’s cool now we’re seeing brands rebel and go back to the small board brands like 3D skateboards, Tired Skateboards, Welcome skateboards, all these little cool brands saying, I want my shit to be different. And they’re doing well — the Poler Stuffs, and the Alex Olson’s and those guys, bringing it back. So really, I’m stoked. It may not be paying well right now, but the creativity is back. And I dig that.

What excites you about photography right now?

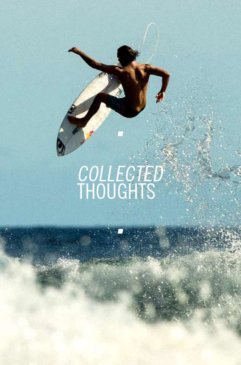

I like good, stylish imaged and I like good photos, but I don’t like hyper-lit, hyper-produced images that look like a Japanese car commercials. I grew up looking at zines and punk rock magazines and punk skate guys. I just recently watched that Thomas Campbell and Rip Zinger episode on Vice. I forgot how much Thomas had influenced me. He got me so hyped as a kid. I forgot to pay homage to Thomas. He’s up there with what I think it should be.

Yeah, he makes beautiful things from what’s actually happening.

Light that’s existing. Elements that are already there. I have a lot of respect for that.

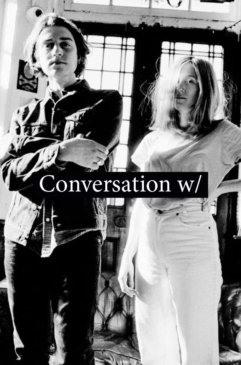

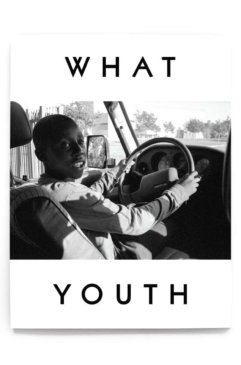

The photos we’re showing are mostly portraits. How did you get into that and what would you say defines your style?

It really stems from punk rock and grunge music and loving like Nirvana and the photos from those old Radar rock magazines. I always remember personalities more than I do tricks. I can always tell you the funny things they said. The connection to the people and the story. They’re all rock stars in their own right, and I want to document them in their moment. I look at Mark Oblow and what he’s done. It’s insane. I’m jealous of his hoarder mentality. I’ve always said to him: this is your work. The stuff you shot in Hawaii at 16. This is you. That’s insane! In 20 years, seeing all that is going to be so important to our culture, and seeing their face and soul it’s a lot more important than a well-lit action shot.

It’s rad that photographers like you have inspired it in kids too. You can see it in submissions here. On Instagram. Facebook. I swear, it’s helped kids document themselves and their lives in this new “me” generation and do it in a rad way. A way that might mean something.

I had a kid ask me to critique his portfolio the other day and he had some flash stuff in there. I said, ‘Honestly, dude, start shooting everything, not just the guy grinding the rail. Shoot it all. Don’t stress on the technical stuff. It doesn’t matter the camera. Or that crap. It’s the story, the soul. The moment.

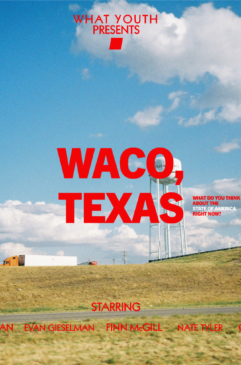

NXT

NXT