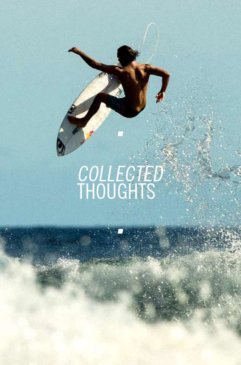

I grew up up watching Kanoa Igarashi surf. He was a true American surf grom in my hometown of Huntington Beach, California. All day, every day. Stickers. Bright, brand-new neoprene. Channel Islands surfboards and KTLA morning news interviews — all by age 10. I watched him go from a fledgling seagull in the shorebreak to dominant male at the peak at the pier. I did interviews with him when he was 12 for the NSSA. He was in the scene. In the heart of Orange County. But today I’m walking behind a very different man. A Japanese man, in fact. Or so it seems.

We’re in downtown Roppongi, a district of Tokyo, following Kanoa through mazes of lights and noise and cigarettes and fish tanks. We’re threading herds of people at intersections that flash and blink, dodging Nigerian men with alleged access to world-class strip clubs that exist somewhere down dark stairwells.

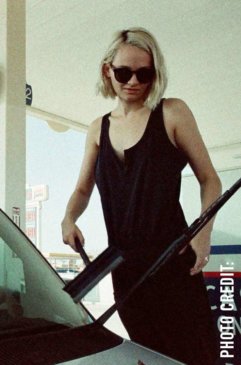

Kanoa is dressed well. Mature for 18, even. He is without his mandatory Red Bull hat. A man of the city. His heavy jacket is accented perfectly by a functional scarf and dark denim. Tokyo is cold in February.

Kanoa is here on a three-day tour of duty for Quiksilver and family before embarking on his first year on the World Surf League Tour. At 18, he’ll be the youngest guy on that tour this year.

We walk inside a sort of four-level nightmare of commerce: level one featuring a massive snowflake eel slithering around a reef aquarium; level two: home goods; level three: sporting goods; and level four is your one-stop shop for anything else the other two didn’t take care of. And if you can’t find what you need here, leave Japan.

Kanoa speaks fluent Japanese and converses freely with everyone we come in contact with. Strangers off the street stop him for photos every 10 minutes or so. We’re on our way to a small underground grill-it-yourself-barbecue fare. Yakiniku it is called.

We descend the steep stairwell of a place you could easily walk right past. This has been my culinary experience in Japan; it is one extreme or the other. Either cheap noodles from 7 and Holding (Japanese 7-11) or you are escorted dawn a stairwell into a beautiful, homestyle restaurant serving the most beautiful foods in a traditional manner. We are getting the latter thanks to Kanoa’s dad. This night has been prearranged. Dinner conversation leads us down tracks of how Kanoa knows pro skater “Figgy” and Thom Pringle and has a network of close friends we could never have imagined.

Then as a variety of meat and vegetables are served, and our glasses are filled, we chat.

WHAT YOUTH: Did your upbringing feel different than most kids’?

KANOA IGARASHI: I think I grew up a little different than most kids growing up in the world. I went to an American school. I grew up as an American. But then at home, I would be speaking Japanese and had Japanese culture, language and food all around me. I think this balance I had of bouncing around from being at school with my friends to going home with my family — it felt like I was traveling from different countries almost. Not just as a kid, even now I still have that balance and I feel in touch with both cultures.

When did you realize that it was unique?

I think I started really realizing that when I was around 11 or 12, when I got on Quiksilver and started traveling. I would come home I would be like, “Ah, I guess I am different than all my other friends.” Yeah I started really realizing it too when a bunch of Japanese media got behind me. Like around 11 or 12 is when I really started feeling it.

How was surfing introduced to you? It seems like it’s been part of your life since you were born.

I started surfing when I was 3. I just remember hanging on the beach a bunch because my dad was a surfer and he’d have his friends and he would always be going down and surfing. And I’d be sitting on the beach all day playing with my mom, and I was sick of not doing anything and seeing my dad laughing with his friends going out in the water. I just was like, “Why can’t I go surf? I wanna go surf.” It was just this thing, back when you were younger your dad was your biggest hero and you want to do everything like your dad and that’s what it was like for me. I wanted to be cool like my dad and go surf.

At what point did that turn into competition?

I did my first contest when I was 6. I was super young and it was a fun thing I did with my dad. It was a “push-in” division. My dad would come in the water with me and push into the waves. I ended up going from the quarters, then the finals, and ended up winning the contest. At the time I was just having so much fun with my dad and I was like, “I won? You can have fun and win?” And I think that’s when my competitive fire was lit.

Kanoa’s family is a tight-knit unit. Nowhere was this on display more than during his traditional sake ceremony congratulating Kanoa for his World Tour qualification — which was attended by Tom Carroll. We’re at a retail store. A nice one. Ron Herman. Drinks and appetizers abound. Friends, media and family are plentiful. Kanoa appears in a suit. I am immediately surprised at the length he goes to stick with tradition. He looks like a man. I am also amazed at the strength of the sake.

Kanoa’s dad Tom has been wearing sunglasses all day. He is nearly Japanese Iggy Pop. Maybe not as reckless, but there is something guru about him altogether.

Kanoa’s little brother Keanu is 13 years old. He is a charmer. Charismatic beyond his years. Affectionate younger brother. Always first to hug and congratulate his older brother. His mother is the family rock. Uniting the Japanese and American elements. It’s all something to see.

We are treated to the polar opposite of this during a visit to Jindai ji in Chofu city, a suburb of sorts outside Tokyo where Kanoa’s uncle owns one of Japan’s most successful Soba noodle restaurants, called Ikyu An.

Once there we escort Kanoa through a series of very ancient rituals and traditions that he does every time he is in town: including a visit to his grandfather’s grave. “Japanese customs are less religious to me, more spiritual, and about tradition and respect.” Kanoa pays his respects to his late grandfather. The Japanese in him coming out more than ever before.

What Are some of your earliest memories of huntington Beach and growing up there?

I just remember a lot of waking up super early because my school started at 8:30. I would have to get out of the water at 7:40. So I would just wake up super early to go surf with my dad. I remember seeing the number of kids who were out in the water with me. A lot were my age and it was just cool to see how many other kids were surfing. I had so many friends in the water who would go to school with me and we’d talk about surfing all day. Probably a big reason why I got so hooked.

When did the Japanese culture begin to influence you more?

When I first started appearing on TV over here in Japan. I was the Japanese kid growing up in America, doing well in contests, and that’s when I really started feeling that I had a lot of Japanese supporters and I really started to feel the Japanese inside of me start to become stronger.

And what are these TV appearances? How does that work and become a thing? Was it random?

It was pretty random. My dad had a lot of connections in Japan. He used to be a pro surfer in Japan as well. He had the connections. I didn’t audition for anything. It just came up and of course, it was an opportunity that I wanted to take, and it was something I hadn’t done before — have a big set of TV people come to America just to shoot this thing on me. It was pretty full on and it went for a while. It was a big learning experience and I think ever since then all my supporters from Japan came from that first TV show.

You’ve been traveling since you were a little kid, often by yourself. Did that ever hit you as strange?

Yeah, now that I think about it. I was a 12-year-old kid going alone to almost everywhere on earth. I went to France, Australia, G-Land, Indo — all those places. But at the time it felt super normal and I felt like that’s what everybody did, and that was a part of trying to be a pro surfer.

Now that I look back at it it’s just pretty weird to have a 12-year-old kid going everywhere alone without his parents. I think it helped me mature a lot more than a lot of other kids, help me see the world, and help my surfing. See different waves, different kinds of people, see unique cultures, and all the food around the world.

What was your educational experience like compared to other kids?

My mom was super strict about education and schoolwork ever since I was really young. She was worried surfing was gonna ruin me going to school and missing days because I wanted to surf. She would always make sure that she was strict enough to where I was going to school, but not restricting my surfing as well. I was going to school a bunch, and I was in honors classes when I was younger. Then it became pretty hard to say no to all these trips I was being offered. I kept my honors classes for about a year into it and then I started doing private school, so I could have more time when I’m home and more of a teacher when I’m on the road. Then two years ago, when I was 16, I got my G.E.D., which is my high school certificate, and that helped me free some time up.

Do you feel like you’ve missed the school thing or do you feel like you made up for it by all the travel and all that?

For me, I learned a lot more traveling. I don’t wanna just say that because that’s what I did and I regret not staying in school, but I feel like I really learned a lot when I was on the road, more than being in my classroom. There were a lot of moments when I had to take care of myself, and there were a lot of times when I had to think it through myself without my parents being there and trying to help me out. I think all those situations that I was in really shaped me.

Do you have any memories or scary moments, injuries, or anything that happened when you were on your own?

I’ve had so many. The ones I really remember are missing my flights alone. I remember one time I was in New York and I was 12, and my flight got canceled and I had to stay alone and live in the city. I’ve had that happen a few times in France as well. My flight got delayed and I thought I had to stay there forever alone. Then I had the time where I broke my leg at Bells when I was 14. My parents were in America and I was Australia with a broken leg, trying to figure out a bunch of stuff on my own, just hospital issues and how to deal with the injury. I had a lot of small moments too where I’m trying to figure out a ride and I had to try and figure out the language to get to another place where all my friends are. It all really helped me even though in the moment it’s terrifying.

Did breaking your leg at 14 freak you out in any way? Like in a bigger picture sense, like. “this could all be taken away from me?”

Yeah, it was weird for me because it wasn’t a thing where it was happening to all my friends, not normal for 14-year-olds to break their leg. Nobody around me was getting injured. I realized, like, “Whoa this could be really bad.” I remember my first doctor told me, “You’ll be lucky to surf again.” And I was like, “Really? You’re gonna tell me that?” I was 14 so I immediately started crying. Now that I look at it I was just a little kid. At the time I thought I was a man and I could handle everything, but then I was like, “Maybe surfing is gonna get taken away from me from this.” Then the next doctor told me, “OK, you’re outta the water for a year.” I’m like, “OK.” That was the best news I heard, “A year? That’s it?” Then I had some time to think. A year is taking a lot outta my surfing and maybe I’ll go back to school and have that for a year instead of just sitting on my butt for a year. There was a lot of stuff going through my head at that time, but then I realized I really did not want to miss any steps in being a pro surfer. I remember working as much as I could during the time I was off, and I felt like I came back stronger than I was before.

What did you do while you were off?

I had to stay in Australia for two weeks after, just for the swelling. I went to America, and after about a week they took my cast off and I went straight into rehab. There was barely anything I could do. I saw a guy, Dr. Sales, in San Clemente. I went in there every day for about four months, even weekends. I spent about five hours a day there. It was like my second house. I probably spent more time there than my house.

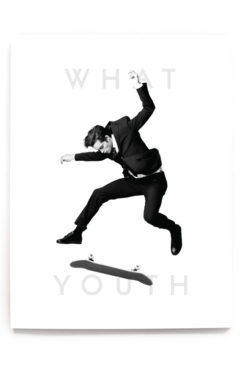

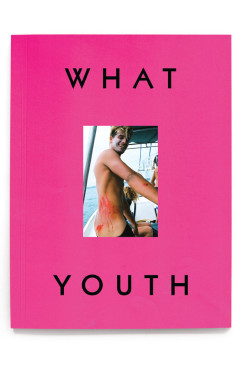

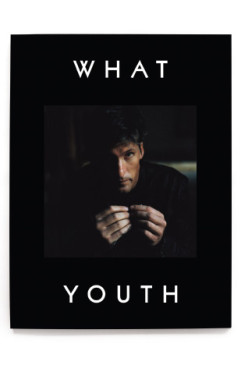

[Read the full interview in What Youth Issue 14, on sale now]

NXT

NXT